Sarajevo – 17th to 18th October 2023

PARIS

MUNICH

VIENNA

JASENOVAC

BERLIN

Sarajevo, a cultural crossroads

While Vienna is sometimes referred to as “the gateway to the Balkans”, Sarajevo and Bosnia and Herzegovina are often called a “meeting place of cultures” and the place where East meets West. This refers to the fact that the territory of today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina was occupied for a long time by the Ottoman Empire and then also by Austria-Hungary; in that time, various religious communities developed within Sarajevo – Islam, Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Judaism – to form a unique multireligious and then also multinational mosaic which can also be seen in the city’s architecture.

The city of Sarajevo was also marked by the dramatic history of the 20th century. In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated during an official visit, leading to the “July-Crisis” between the European powers gathered in antagonistic coalitions, and then to the outbreak of the First World War. During the Second World War, Sarajevo was occupied by Nazi Germany between 1941 and 1945, before being liberated by the Yugoslav partisans in April 1945. And during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1995), Sarajevo was besieged for three and half years, the longest siege of a capital city in contemporary times, what left an indelible mark on the city and its population.

As a place, which combines the legacies of the First World War, the Second World War, and the violent break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the discovery of Sarajevo is therefore closely linked to our topic, “War(s) in Europe. Shared experience, collective memory? – Germany, France, Bosnia and Herzegovina”.

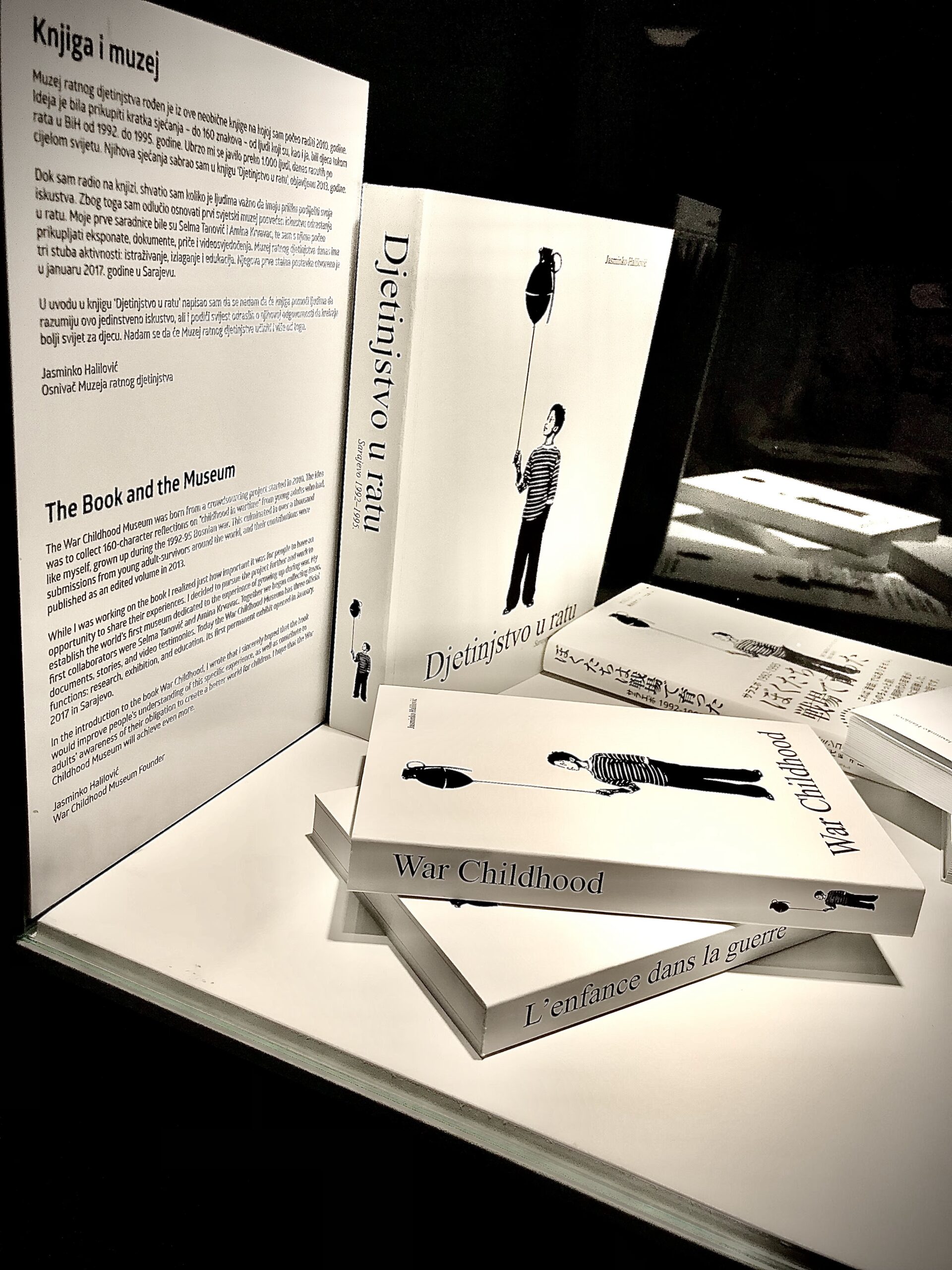

War Childhood Museum, Sarajevo

Urban discovery of historical landmarks

- Sarajevo City Hall (Vijećnica): a magnificent Austro-Hungarian construction built in the so-called “neo-Moorish style”. It served first as the city hall and, during socialist Yugoslavia, as the National Library and became a symbol of the city’s rich cultural and historical heritage. It is also for this reason that it was deliberately destroyed by the nationalist besieging forces in 1992, before being rebuilt in the original style in 2014.

- Baščaršija: the old bazaar and historical centre of Sarajevo, which reflects the city‘s Ottoman heritage with its cobbled streets, traditional crafts, and historic buildings.

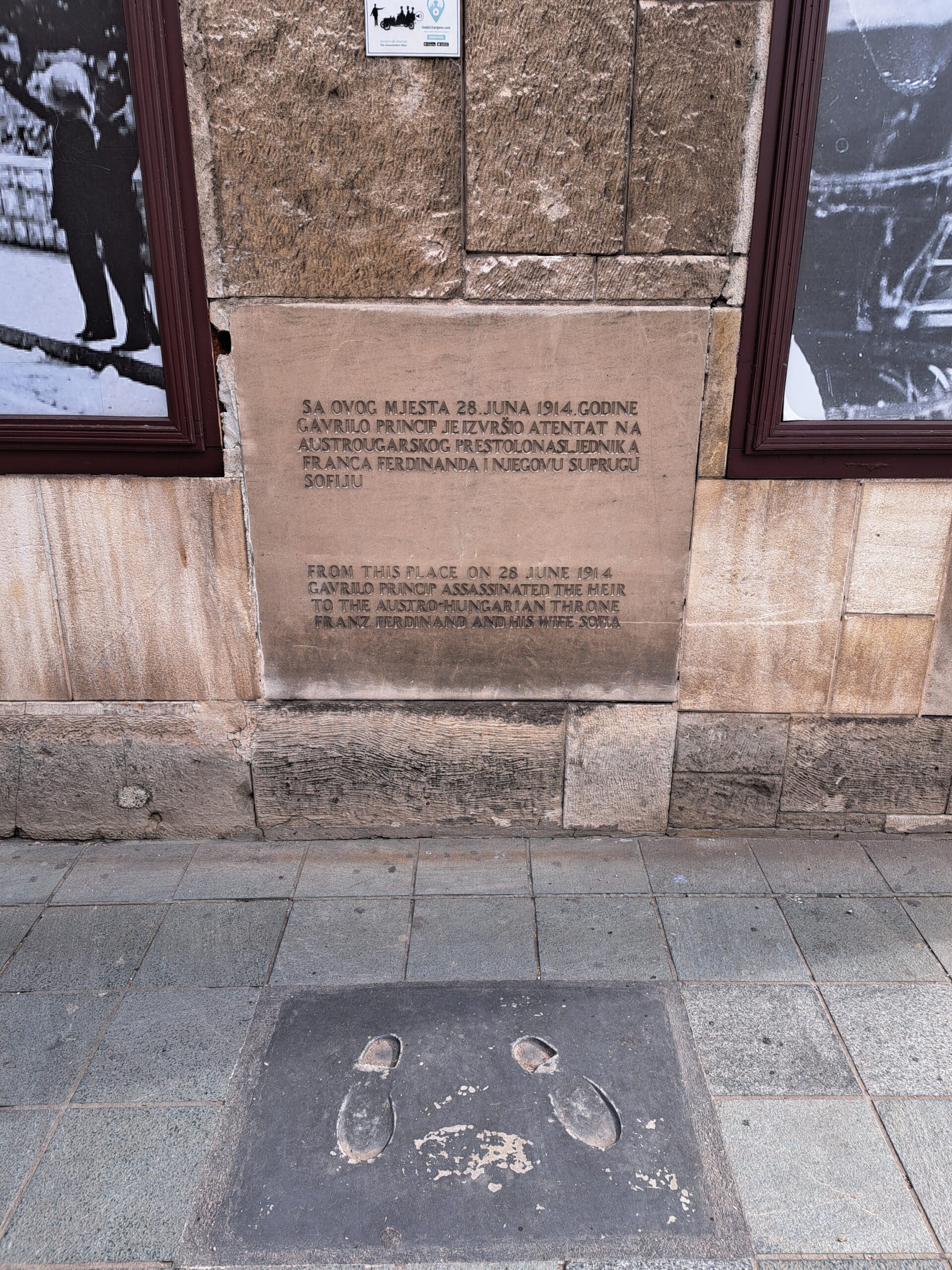

- Latin Bridge (Latinska Ćuprija): the place where Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in 1914 during his official visit.

- Eternal flame (Vječna vatra): a monument erected in 1946 to commemorate the liberation of the city on 6th April 1945 by the Yugoslav Partisans from the occupation by Nazi Germany; it is dedicated to the Muslims, Serbs, and Croats who fought together in the Partisans Army.

- A memorial plaque near the Orthodox Church where the city of Sarajevo thanks the citizens of Barcelona for helping Sarajevo during the 1992-1995 siege. The solidarity of Barcelona with Sarajevo at that time was inspired by the fact that both towns had hosted Olympic Games (Sarajevo in 1984, Barcelona in 1992).

- “Susan Sontag Square” in front of the National Theatre: the theatre square was renamed “Susan Sontag Theater Square”, in reference to the famous American philosopher who visited Sarajevo several times during the siege. During one of her visits, she staged the theatre play “Waiting for Godot” with Sarajevo actors, symbolising Sarajevo’s waiting for an intervention by the international community to end the siege.

- “Olga and Suada bridge”: on the 5th of April 1992, huge demonstrations took place in Sarajevo to protest against nationalism and the possibility of war. But snipers fired on the demonstrations and two women were killed on this bridge, who are considered to be the first victims of the siege of Sarajevo, which began de facto on that day and lasted for three and a half years.

- The ICAR Canned Beef Monument in Marijin Dvor, a large representation of a can of beef, which was part of the goods distributed by international organisations to the population during the siege. The inscription reads: „Monument to the International Community – The grateful citizens of Sarajevo“. Erected in the framework of a project on “Counter-Monuments”, this ironic monument refers to the fact that the UN brought humanitarian aid to the besieged Sarajevo (including food of an often dubious quality…) but, at the same time, refused a military intervention to end the siege.

The group in front of the Sarajevo City Hall.

Resilience of Sarajevo’s inhabitants during the siege

The city walk ended at the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where we first looked at photographs, which show the daily life during the siege. Not only were the city and its population regularly targeted by grenades and snipers, but most of the time, the city was also deprived of electricity, gas and running water, creating extremely harsh conditions for daily life. In the museum, we then looked at several objects which citizens of Sarajevo made themselves to cope with the catastrophic situation, for example little ovens made out of cooking-pots to heat a room in winter. During the workshop, we talked then mainly about the resilience of the inhabitants of Sarajevo who refused to give in to the violence imposed on them during the siege. This resilience reflected not only in their ability to invent and create ways of surviving on a daily basis, but also in what is called “cultural resistance”. During the siege, a lot of cultural activities were organised by and for the people of Sarajevo, including concerts, theatre plays, exhibitions, literature events, … This was a crucial way to live normally in an abnormal period and to use culture as a weapon against violence. This cultural resistance involved people of all religious and national backgrounds – many of whom considered themselves primarily as citizens of Sarajevo, not as members of ethnic communities – and it was also partly supported from outside, as the example of Susan Sontag shows. We talked also about other examples of international solidarity by ordinary citizens and cultural actors from other European countries during the Bosnian war. Indeed, while European governments remained passive, refusing to intervene to end the siege and the war, and most people in other European countries remained also indifferent, many individuals and groups happened to refuse this indifference, criticised their own governments and tried to take action in different ways.

Today, nearly 30 years after the war, Bosnia and Herzegovina is a highly fragmented country, politically dominated by different and competing nationalisms. These nationalisms have also influenced Sarajevo, but a spirit continues to exist, defending the city’s multi-ethnic and antinationalist identity and insisting on the importance of living together. During the siege, despite and in contrast to the violence, everyday life resilience, cultural resistance as well as solidarity between inhabitants and solidarity from outside were crucial for survival, not only physically, but also spiritually and mentally. The example of Sarajevo invites us to consider topics and questions that are also essential for other conflicts in the contemporary world: how to survive physically and mentally in a war situation? How to preserve humanity and community life in war times, despite and against nationalism and violence? What role can culture play in this battle? How to show solidarity in times of war? What can I do, as an ordinary citizen, to support other people in a war situation and threatened by daily violence?

Author: Dr. Nicolas Moll